Sometimes the smallest things can have the biggest impact. Other times, they remain just small things. Whether the introduction of an invasive plankton species will have a large, medium or nearly unnoticeable impact on the health of Lake Winnipesaukee is something experts say remains to be seen.

The invasive species in question is known as the spiny water flea, scientific name Bythotrephes longimanus. It is an animal native to Europe and Asia, and was first discovered in North America in Lake Ontario in 1982, likely spread across the Atlantic Ocean accidentally in the ballast of a cargo ship. Since then, it has been observed in waterbodies throughout the northern United States and southern Canada, and in lakes as near as Champlain, in Vermont, and George in New York, according to a press release issued last week by the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services.

There’s no direct harm presented to humans by the spiny water flea. However, it has the potential to change the ecology of the lake, and in ways that most humans would find undesirable. Then again, there’s also the potential for the introduction of the new species to find a natural balance within the lake’s ecosystem, and any impact might be negligible. But it's too soon to tell.

The state DES exotic species program has been keeping an eye out for several years, anticipating the spiny water flea’s debut. That monitoring has been led by DES scientists Kirsten Hugger and Amy Smagula, who survey Winnipesaukee by dropping a cone-shaped plankton net down to the deepest parts of the lake, then pulling it back up to the surface. The net funnels plankton-sized and larger particles down to the point of the cone, where there’s a collection jar that allows water to drain while trapping the specimens.

This summer, after several years of monitoring, Smagula and Hugger pulled in a specimen jar that looked different than all the others before. In it was a zooplankton bigger than Winnipesaukee’s native plankton and, trapped in a jar concentrated with other plankton species, the big newcomer was excitedly moving about, feasting on its neighbors.

“It was a little surprising, after monitoring for eight years and not finding it. You assume it’s going to be another good year,” Smagula, a limnologist, said about that moment. “We both looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, shoot!’”

Hugger, an aquatic ecologist, said she and Smagula identified nine deep-water locations around the lake to monitor. So far, they’ve found spiny water fleas at three of the locations — one in Gilford, one in Alton and one in Wolfeboro. They have continued to pull samples containing the spiny water flea from those sites, and will monitor other parts of the lake, too, to track how the population spreads, and how dense it grows at places where it establishes a foothold.

Murky future

It’s very likely the spiny water flea was brought to Winnipesaukee by anglers or recreational boaters who took their boat out from a water body such as lake Champlain or George and launched it without following the clean-drain-dry protocol. During that process, boaters drain their bilges and live fish wells, and clean off any mud or plant fragments from their boat exterior or fishing gear before leaving the water access area. Environmental groups advocate such practices as a way to interrupt the spread of invasive aquatic organisms.

Hugger, and others interviewed for this story, said it’s far too early to say what the introduction of the spiny water flea will mean for the Lakes Region. However, there is reason to be concerned.

“We are going to continue working with Fish and Game and monitoring for this. We don’t fully know what will happen to the lake,” Hugger said.

DES will be monitoring how far the flea spreads, and how dense those populations grow. They’ll also be looking for how its growth affects the mix of native plankton species, because a disruption in that population could send shockwaves through the food chain.

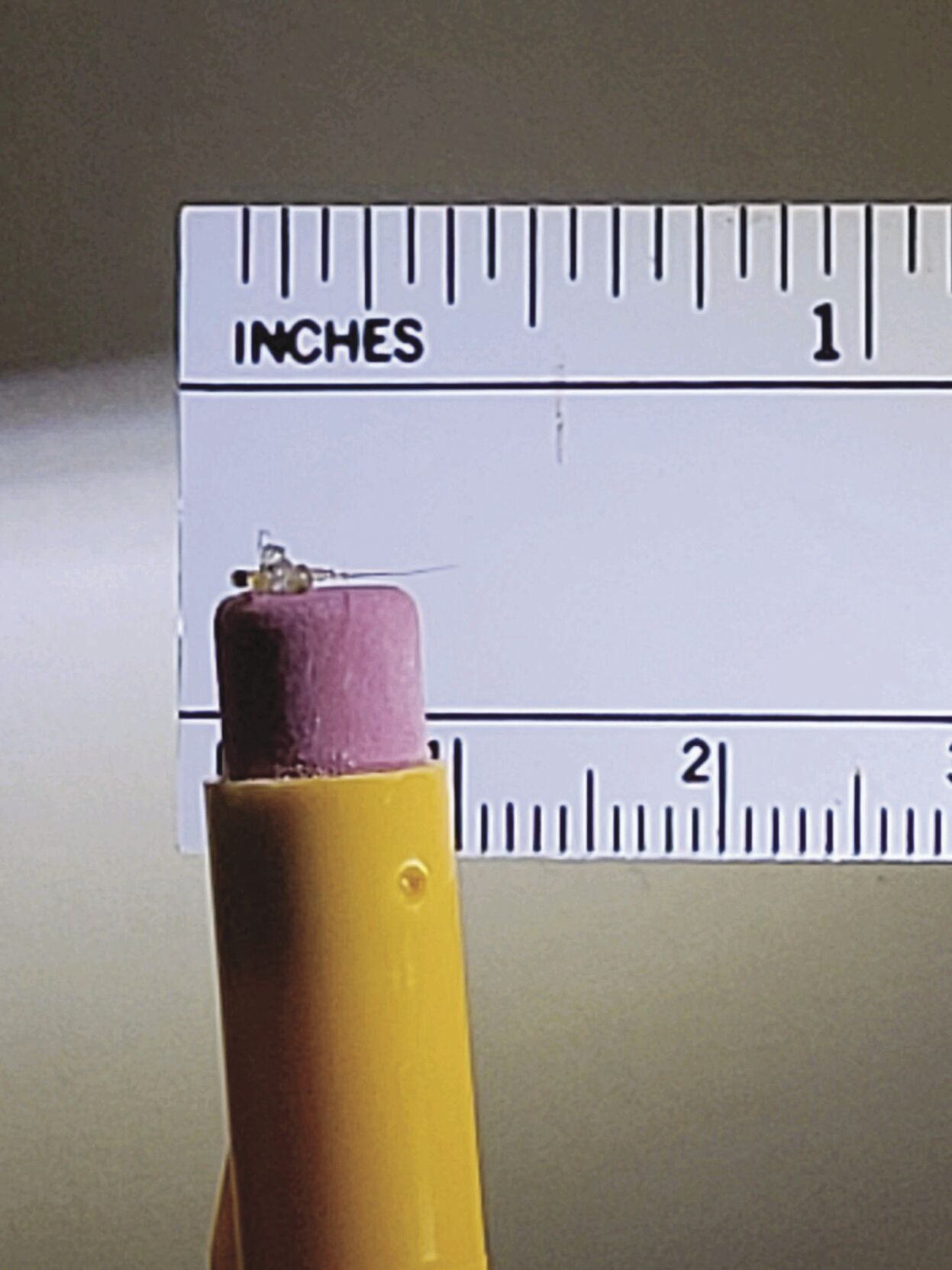

Spiny water fleas, about a centimeter in length, are larger than native plankton. They’re also a predatory species, which feed on the smaller plankton. Some of their prey species include a native plankton called daphnia.

The daphnia are an important player in the Lake Winnipesaukee ecosystem. Daphnia eat algae, and in doing so, help keep the lake clear. They are also an important food source themselves, often providing much of the dietary needs of small bait fish, such as rainbow smelt, which are, in turn, important food for larger fish.

In the range of possible outcomes, a booming spiny water flea population could result in a lake where there’s more algae and fewer fish. In water bodies where the fleas have proliferated, they have sometimes formed floating masses in the waterways, and have congealed, like wet bolls of cotton, around fishing gear.

“So, it can be unpleasant,” Smagula said.

But it hasn’t come to that in every water body where the spiny water flea has appeared.

“The research that we’ve been finding about fish is really a mixed bag. It appears that this could be not great for young-of-year fish. The spiny water fleas have such long, spiny tails that it makes it extremely hard for young-of-year fish to feed on them. But there is evidence of larger fish being able to eat spiny water fleas just fine,” Kirsten said. “I don’t think we can predict how this will affect the fish community.”

At the Department of Fish and Game, inland fisheries supervisor John Magee said they’re in a “wait-and-see” mode regarding the flea. There isn’t any other option, really, because there’s no way to control the population.

“What we do know is that our friends over at DES have been monitoring for this species in Winnipesaukee for a number of years. When it was found, earlier this year, it was at really low levels. ... The problem is, we don’t have an answer to say, ‘Oh, this is devastating,’ or, ‘Oh, it’s not that bad.’ You don’t know until the great experiment of life has played out.”

Fisheries biologist John Viar said he was taking a similar approach.

“We’ll see what happens, because there’s not much we can do,” Viar said.

Most of the game fish in Winnipesaukee are not native, and are only present in the lake thanks to hatching programs run by Fish and Game. Even so, the spiny water flea could potentially hobble the state’s ability to keep the lake full of salmon, rainbow trout and other fish. The state stocks the lake every year, but with small fish that need to grow for a year or two before they’re large enough for anglers to keep.

Biologists such as Viar use sonar to survey the lake prior to stocking, in order to measure the availability of bait fish. The survey informs Fish and Game as to how many game fish the lake can support. If the spiny water flea causes a collapse of the bait fish population, the state won’t be able to compensate by releasing more game fish, because those fish wouldn’t have enough food to grow into a catchable size.

As Magee put it, “We can’t just stock our way out of it.”

That scenario is only one possibility, though, Viar cautioned.

“We don’t want anyone to panic,” Viar said. There have been other invasive species scares in recent history, he said. Yet Winnipesaukee has remained a vibrant fishery and is busier than ever with recreational activities.

The takeaway (or don’t takeaway)

Lake Winnipesaukee drains into the Winnipesaukee River, which then flows into lakes Opechee, Winnisquam and Silver, eventually joining the Merrimack River. There’s nothing to prevent the spiny water flea from going with the flow of water and finding new territory downstream.

But there are plenty of other local bodies of water that are not downstream of Winni, and Bree Rossiter, conservation program manager for the Lake Winnipesaukee Association, said there’s still time to prevent spread.

“It’s even more important for boaters and other water recreationalists that they practice really good lakes stewardship,” Rossiter said. “Make sure that they’re keeping an eye on the water, reporting infestations. But even more, if they are coming into Winni, or leaving Winni and going into another lake, that they do the clean-drain-dry.

“Just be aware and wash off any water-related equipment, check fishing lines, bait boxes, anything like that,” Rossiter said. It’s possible the spiny water flea has a limited role in Winnipesaukee, but a devastating effect in a different body of water. If there’s no small fish, there’s no big fish, and then there would be no fish-eating birds such as eagles or herons.

“It’s disrupting the balance of that ecosystem, potentially having cascading effects on that whole ecosystem.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.