When an eating disorder arises, parents shouldn’t blame themselves or their children, said Beth Shehadi, a counselor at Plymouth State University who treats college students with eating disorders.

“Nobody asks for an eating disorder. It’s a way of coping,” she said. “Eating disorders thrive in darkness. People with them are very private. They say, ’I’m not going to tell anyone about it. I want to stay thin.’ They’re uncomfortable but not willing to give up the behavior.”

Sometimes Shehadi relies on images from Harry Potter to sprinkle seeds for change. “Think of the eating disorder as Voldemort, and Harry has to defeat him by killing off the horcruxes.”

Counseling helps patients build a healthy sense of self, she said. “I look for people’s strengths, and things they’re interested in. Validate them for really little things, like going to classes and coming here voluntarily.” It’s important to be non-judgmental and very supportive, she said, to repeat validations and affirmations over and over. “It’s not a quick fix, but recovery is possible.”

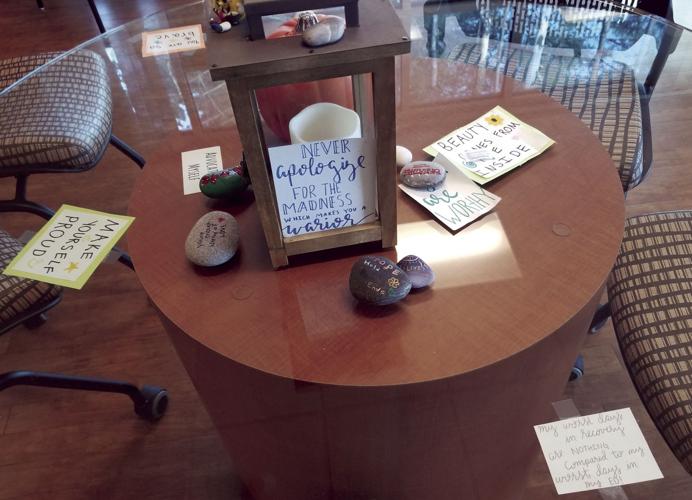

Recovery happens at places like the Reflections Eating Disorders Center in Salem, where sun filters through a bank of windows overlooking the woods in changing seasons. Words of encouragement are scrawled on slips of paper visible through the glass tops of dining tables in the center’s café.

An adjacent room hosts yoga and art-making, dance parties and music classes during which patients compose and sing songs they’ve written together. Mindfulness walks help them slow down and pay attention to their surroundings.

At first glance, Reflections seems more like a pampering day spa or a wellness club than a treatment center for people with a serious mental illness.

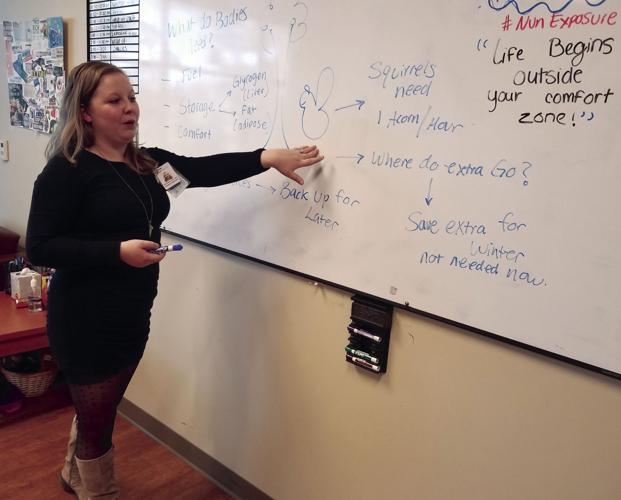

Here, in addition to group and individual therapy, supervised meals and snacks, and tutoring in self-calming and redirecting one’s thoughts, patients receive instruction on how their minds and bodies are dictating their behavior. They learn how eating disorders affect their neurotransmitters, and how changes in those levels determine their appetites, self-perception and thinking. They learn to set goals and live in the present as they strive to end habits such as restrictive eating, purging and excessive exercise, which can prove fatal if untreated.

“We explain a lot of the medical science. People learn that they can’t control how their bodies function. They refocus on things they can control,” said Breanna Mears, the center’s dietician. “We’re empowering them by debunking what they hear on Good Morning America or through diet culture. We give them the facts, instead of the fads.”

Treatment

Two years ago, Reflections became the third facility in New Hampshire offering intensive day treatment for eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and others that may not meet the strict definition of any single type.

“There are people with eating disorders that don’t meet [specific] criteria, but are just as sick,” said Ruth Elliott, executive director of Cambridge Eating Disorder Center in Concord, a subsidiary of a longstanding program outside Boston.

CEDC Concord regularly treats Lakes Region patients. The state’s other intensive day treatment program is the Center for Eating Disorder Management in Bedford.

Eating disorders are a silent epidemic today, experts say — a public health concern often overshadowed by the opioid crisis and other forms of mental illness that garner more media attention and research funding, such as schizophrenia, which affects fewer people and has lower mortality rates, according to statistics from the National Institutes of Health.

“People who are struggling with binge eating disorder have a harder time going into a treatment center. It’s so under-reported,” said Elliot. “They feel a higher level of shame.”

American diet culture has a lot to do with the surprising prevalence of eating disorders, especially binge eating disorder, she said.

“Any time you take away food, it’s going to lead to bingeing. Yo-yo dieting leads to people having a higher weight,” she said.

Help for eating disorders can be scant, especially in rural areas. Treatment tends to be concentrated in urban areas, and the number of trained mental health and medical practitioners falls short of increasing demand, according to the National Eating Disorder Center. This results in longer waits for treatment, which in turn can lengthen recovery time.

“That’s a huge issue in our state, finding individual providers, nutritionists and therapists,” Elliot said. “We need to create a better network of providers. When [patients] come here, it’s really hard to refer them out to someone in the community when they discharge."

Practitioners who receive specialized training through the eating disorder certificate program at Plymouth State University “are not settling in areas that need help the most,” Elliot said. “We get a number of calls from the Lakes Region and up north. Resources decline as you go north.”

National experts say eating disorders are affecting younger patients, and more men, older adults and middle-age women are seeking treatment. At CEDC in Concord, most patients are clustered between the ages of 15 and 17, and the early 20s to 30; parents of a five-year-old recently called to find help.

Unique approach

Between February 2018 and mid-fall, Reflections treated 120 patients between ages 12 and 64, mostly from northern Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire, and occasionally from elsewhere in New Hampshire.

Reflections, which is part of Parkland Medical Center’s Salem clinic, is unique in the state in that laboratory and diagnostic testing and iron infusions are available down the hall or one floor above, eliminating time and travel for blood work and other medical assessments. Reports can be available within hours, similar to the turnaround time at a hospital. Discount rates are available at local hotels for people who live too far to commute to Reflections’ intensive outpatient or partial hospital programs, which run three to five days a week, three to 10 hours a day.

Monika Ostroff, the Reflection’s first director, said its therapy and treatment plans are tailored to individuals, and are not generalizations of what works for most members of a given patient group. Personalized exposure therapy targets situations where each patient struggles, such as eating pizza with friends, preparing for a job interview, eating in public places or shopping for clothes.

Rehearsing triggering situations and learning to cope forges a smoother transition to daily life, Ostroff said. Patients exit the program armed with self-control and positive thinking strategies to defuse their stress around food and body image reminders.

“When you have an eating disorder, you’re exposed to ads 3,000 times a day” through mainstream and social media, from a society that praises physical fitness, health and appearance. “A lot of time you’re trying to protect yourself from things that make you worry about your body” and not eat, Ostroff said. “There’s going to be something during the day that’s going to trigger the eating disorder you have.”

When patients arrive, they’re often compromised by starvation or seesaw eating that has caused nutritional deficiencies. Systematic refeeding helps them become physically and mentally sound. At that point, self-destructive mindsets can be changed.

Therapies

Embody therapy helps patients learn to move joyfully in their bodies instead of focusing on exercise to burn calories and lose weight. Acceptance commitment therapy, which involves mapping goals on a target and seeing how close one’s behavior comes to the bullseye helps them define goals and decide whether their behavior is bringing them closer to a desired outcome.

“It helps them detach some of their emotions from reality and be a little bit more objective,” Ostroff said. “They see how their eating disorder is interfering” with present happiness and future plans.

A hopscotch-like game of squares outlined by strings helps patients quickly recall coping skills in unpleasant situations, such as accidentally seeing their weight on a scale at a doctor’s office after not knowing for a long time.

“You’re blindfolded because you don’t always know what’s in your future. It’s symbolic of what happens to us during the day. This game allows you to practice reactive problem-solving skills in real time,” Ostroff said.

Counselors accompany patients to real-life exposures that spark a flood of bad feelings or thoughts. Patients have said, “All my friends go to Starbucks and have a frappuccino, and I’m terrified of what it’s going to do to my body,” Ostroff said. “This meets patients where they’re at and helps them integrate what they’ve learned and know they’ll be OK.”

People who’ve become addicted to rigid routines and are governed by repetitive, intrusive thoughts learn to become more flexible, open-minded, and self-forgiving. Especially in anorexia, which is a condition characterized by perilous levels of exercise and food restriction, “one of the things you’ll see is how they prioritize what they do is extremely important. They can’t get themselves off the exercise machine to answer the phone. They think they need to work out for 30 minutes and they’ve only done 28. They will have heart palpitations and they still can’t get off,” Ostroff said.

Acknowledging the problem

It can be challenging to get people with eating disorders to admit there’s a problem, and sometimes it’s years before they seek help, experts say.

“It almost looks normal or favorable in our society,” said Elliot. “So they suffer for a really long time.”

Among women who come for treatment in their 30s, “half of these people have had an eating disorder that was not diagnosed when they were young.”

Symptoms of eating disorders in people of various ages include failure to grow, loss of menstruation, persistent stomach aches, social isolation, body image obsessions, mirror-gazing, frequent or lengthy visits to the bathroom, as well as eating rituals: same food, same time of day, measuring portions, counting calories, retreating after meals and eating alone, eating very slowly and throwing out food, according to the Cambridge Eating Disorder Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wrappers and containers may be squirreled around the house.

Kate Rodrigue, a nurse at Laconia High School, notices changes in weight and appearance on students, who may also be lethargic and pale.

“It’s important [for parents and students] to reach out and ask for help at the very first warning signs, even if they’re not sure,” she said. An eating disorder “can go under the radar until it’s been there for a while, and then it’s difficult to treat.”

One former Reflections patient from the Lakes Region, who declined to be identified for fear that she might be recognized, said she struggled with anorexia since she was 10 or 12, and didn’t start getting help until her final year of high school.

“I thought it was a waste of time to see a therapist. I was bullied a lot through school” and she struggled with low confidence and self-esteem.

She now sees an outpatient therapist weekly, and a primary care provider and nutritionist to maintain her physical health.

It’s essential to realize “You’re not alone in this and there is always help out there,” she said. “You don’t have to struggle alone. Reach out for the help because it will be worth the hard work in the end. Don’t give up.”

•••

The Sunshine Project is underwritten by grants from the Endowment for Health, New Hampshire’s largest health foundation, and the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.

Contact Roberta Baker by email at Roberta@laconiadailysun.com

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.