LACONIA — What do you do when you find an abandoned, overgrown cemetery, the markers for those interred inscribed only by number?

That’s the question now faced by Belknap County, members of the public, and experts on gravesites and cemeteries. Luckily, some of those same people have ideas for solutions.

When Lois Kessin was a child, she remembers walking in the woods near Primrose Cemetery often. One day, she stumbled upon what was clearly an abandoned cemetery, completely overgrown with brush, the headstones hardly visible — let alone legible.

The industrial area of today was only woods and empty fields at the time, except for the county jail which was located in the same spot as the contemporary facility.

“I would wander to those woods, climb those trees, disappear all day long,” Kessin said.

Immediately, she ran home to her father upset, having noticed many of the headstones displayed no names. Only numbers.

It was the 1950s, to the best of her recollection, and her father explained it to her: those were pauper’s graves. Inside were interred the county’s poor, a common practice from another time.

Kessin was struck with melancholy for those who’d been long forgotten.

“I just thought it was awful to give people numbers and not names,” she said. “All my life, I’ve thought about that moment and how my father explained it to me.”

Around 70 years later, the cemetery — located along the modern Primrose Lane, at the northwest corner of a parking lot in the north end of the city right next to a horseshoe pitching court — is well-suited for a facelift. Its existence was brought to the attention of county staff by a group of locals who, like Kessin, are seeking to right past wrongs.

Walking through the cemetery today, a visitor would notice over 100 graves, the first four rows with names and dates. The rest — 60 some-odd resting places — are identified only by number. The plot, a quarter-acre in size, is just shy of 40 paces deep and 17 paces wide.

Prudy Veysey of Gilmanton became aware of the cemetery's existence just shy of two years ago from a friend whose family worked in that area. She set out to learn as much about it as possible, and within weeks reached out to Kessin and others. She then brought it to the attention of Jon Bossey, facilities director for Belknap County.

Bossey’s been in the job about two years, and said he was not aware of the primitive cemetery located nearby the county complex off North Main Street. He’s seeking funding from the county delegation in his department's budget proposal to revitalize the cemetery, describing it as a responsibility of the county he feels strongly about.

“It is important to mention that this was not vandalism, it was just neglect,” Veysey wrote in an email. “It seems as though no one was aware of this cemetery.”

Within it lie residents of the county farm, a relic itself, enshrined nearly only in memory.

Veysey, in the immediate term, gathered a group of friends and set to work, clearing brush and fallen trees to restore the parcel to at least a shred of dignity. They’re hoping, through hard work and care, to bring it up to a respectable standard with the help of the county.

“Prudy reached out to me,” Heidi Preuss, a friend of hers, said. “She was the chief organizer of the event.”

The first cleanup occurred Oct. 18, 2023 — Preuss, Prudy and her husband Warren Veysey and Kessin worked there alone.

“I called them and we did it immediately,” Prudy said.

“It wasn’t a 'committee' or even a discussion,” Preuss, who’s visited other pauper’s graves around the country, said.

“It’s sad in that sense, that it had been neglected — it’s just hard.”

The group cleared brush and “made a mountain of debris”. They brought landscaping equipment and “worked all day”, mowing, raking, weed-whacking and pulling weeds. They piled the brush on a fallen tree.

Working with Bossey, a group of inmate volunteers from the jail and county employees set out to remove the debris.

Prudy and Warren returned later in October to plant 150 daffodil bulbs at the site.

“It looked pretty good when I went over in October,” Prudy said. “I think it’s back in the [county commissioners'] hands.”

Prudy said she’s grateful for the help received from Bossey and the county, and hopes the cemetery is properly adopted so descendants are able to identify family members buried there to pay their respects.

What was the county farm?

In attempting to learn more about the cemetery, Kessin suggested Prudy reach out to Virginia Hansen, who manages both Bayside and Union cemeteries, and is an expert on gravesites in the area and the Belknap County Farm.

Hansen gathered quite the catalog of information and has given numerous presentations on the county farm’s history. The county purchased 148 acres in 1853, from Mary E. Boynton and Betsey S. Boynton, heirs of Stephen Boynton, who managed it as his homestead. Soon thereafter, the property became home to Belknap County’s “poor farm” and jail.

So-called “poor farms” were common throughout New Hampshire in the 19th century, particularly before 1866, and after that year the state required each county to organize one.

“Every town had a 'poor farm' at one point,” Hansen said Thursday afternoon.

The original Belknap County Farm burned in 1871, leaving about 150 acres of barren land in its wake. In 1872, new facilities were constructed. In the proceeding years, the county purchased more land and made improvements to existing buildings and constructed a county jail — the jail today is located on the same parcel.

At this point, the county farm provided housing and work for the poor, the mentally ill and those convicted of crimes. At the facility were also a doctor and a chaplain who served the residents. The Belknap County Annual Report contains extensive records of the activities at the farm, and shows they often turned a profit, selling crops they’d raised over the year.

“It was kind of all of it,” Hansen said. “A lot of people confuse it with the State School — it was not the State School.”

According to county records, the county farm supported between 34 and 42 “paupers” through the 1860s at a cost between $1,800 and $2,200 per year.

In 1945, the county farm became the county home, and by the 1960s — after welfare legislation was broadly adopted — county farms were no longer deemed necessary to support the local indigent population, and gradually disappeared.

Now, there’s something of a mystery — county farm records include the creation of what’s now referred to as Primrose Cemetery in 1873. That cemetery was borne out of necessity, when an older cemetery ran out of space. That cemetery, likely located somewhere near the land currently home to the county complex, hasn’t been found.

Who’s buried at the County Farm Cemetery?

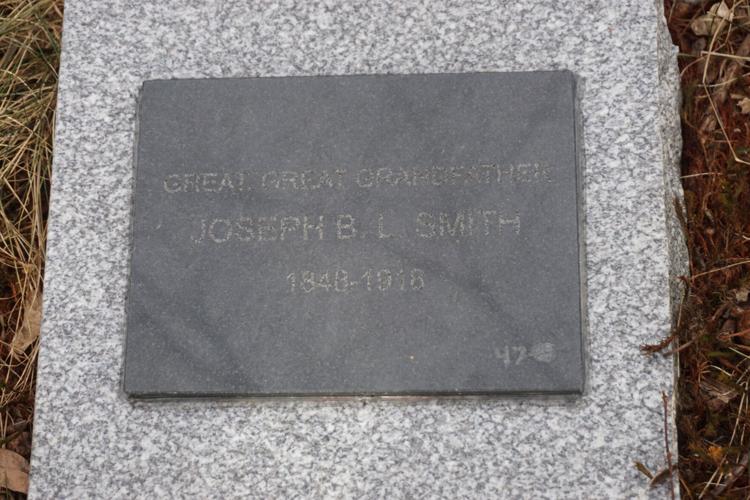

Basic information about Primrose Cemetery is known. There are 42 headstones, located in the older section of the cemetery towards the north, which denote names and dates of death. The first burial in this portion of the graveyard was of Benjamin F. Follins — he died Feb. 13, 1873, at age 68. The last stone was named for Eliza Burleigh, 70, who died Jan. 26, 1892.

Those buried there were likely county residents who had no kin able to claim their remains for private burial. It’s truly a countywide burial ground, representing numerous modern-day towns and cities throughout Belknap.

By 1894, the county began using numbered headstones for burials there, and today you’ll find 60 of them. Hansen has made great strides in identifying the numbered burials, and her contribution to the Fall 2022 edition of The New Hampshire Genealogical Records documents the names of over 100 interred at Primrose Cemetery, 62 following the county’s use of numbered headstones.

Hansen was able to document them through various methods — the state’s vital records office in Concord, annual reports which list deaths at the farm and kept by officials of Laconia, and through searching records held by Ancestry.com.

Now, those interested can check if they’ve got a relative buried there by finding Primrose Cemetery on findagrave.com or reading Hansen’s abstracted contribution to the New Hampshire Genealogical Records.

“We would like to thank the residents of the county jail for volunteering to continue our efforts,” Veysey said.

“Our heartfelt thanks to Jon Bossey for his careful management and care of Primrose Cemetery.”

(2) comments

I found that cemetery years ago & was told that it was the poor folks from the county home that had no family or money . It’s a sad site with the graves sinking in & no names very sad .

When I was a teenager, I recall a Mr. Holman who works for the Laconia cemetery department. He told me of a cemetery off Blueberry Lane, near where the old Laconia airport once stood. I never found the cemetery. I was told that the land was developed, and the cemetery was covered over. Are these just rumors?

There is another abandoned cemetery off Meredith Center Road just North of the city dump on the east side. You would find an abandoned road. There is many gravestones. I can barely make out the inscriptions. Anyone know about this?

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.