For most, the discovery of human remains would be a gruesome if not traumatic experience. For a select few, it’s why they go to work in the morning.

It may not be something that most people like to think about, but there is a system of professionals who are trained and experienced to respond when cadavers, or even just bones, are found, usually by unsuspecting hikers, hunters or anglers.

Not that it happens too often. In fact, said one law enforcement professional, it’s surprising how quickly creatures of flesh and bone are absorbed by the Earth.

Consider all of the wild animals who perish in the woods, said James Fogary, lieutenant with the State Police and commander of Troop E. Yet, finding an animal carcass is a fairly rare event, even for people who spend a lot of time exploring the outdoors.

Finding human remains is similarly rare. Lieutenant Brad Morse, Fish and Game Department, said he can go for a few years without investigating human remains in his district, which takes in 34 towns including all of Carroll County. Yet there have been periods where a few will be discovered within a fairly short time, and this seems to be one of those periods.

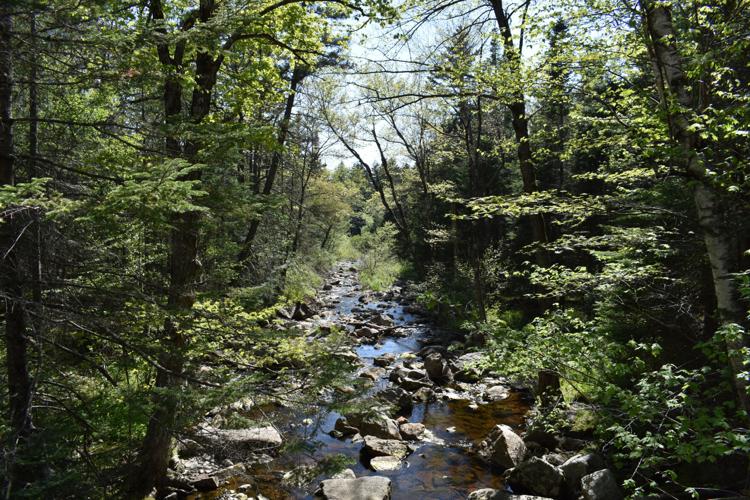

In November, human remains were discovered in Gilford, on the grounds of the Laconia Airport. Gilford police report that they are still waiting for forensic results to determine the person’s identity. On May 2, fishermen found human bones scattered through a remote area off of Sandwich Notch Road, and authorities say it will be months before they hope to be able to say who the bones belonged to.

Chief medical examiner

In cases such as these, the remains are brought to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Dr. Jennie Duval, of the OCME, said state law prescribes that all “sudden, unexpected or non-natural deaths” are investigated by her office. That includes decomposed or skeletonized remains. Duval said that her investigations begin with an examination of the death scene, which can be a challenge depending on where those remains are discovered. The scene is usually searched using the help of canines, and of prime importance would be any personal effects that could assist with answering the principal questions: Who was the person, and when and how did they die?

“Human remains are only rarely discovered in wooded areas of New Hampshire,” Duval said. More commonly, large, isolated bones are discovered by homeowners or their pets when digging on their property, which her office usually determines to be non-human in origin. Or, large excavation projects might discover unmarked historic graves, which become the purview of the state archaeologist.

If bones are determined to be likely human, they are sent to a forensic anthropologist. “The anthropologist may be able to provide an anthropologic profile (race, sex, stature) and detect disease processes that can assist in identification,” Duval said. The analysis might be cross-referenced with other data, such as dental or medical records.

If the complete skeleton is recovered, if it was protected from the elements, and if there are other personal effects also found with the remains, the job of identifying the remains becomes easier. If a positive identifcation can be made, the remains are released to the decedent’s family. If not, the remains are stored by the OCME until further evidence surfaces that can help fill in the puzzle.

Part of the reason why these identification processes can take many months is due to a backlog at the laboratories that process forensic DNA, and at the offices of the scientists that analyze the remains.

Duval said that one of the forensic anthropologists that her office works with is Dr. Marcella Sorg, a research professor at the University of Maine.

Sorg said that analyzing human remains is something of a side gig for her; her primary vocation is in public policy and epidemiology. Even so, she said she has analyzed “hundreds of cases” in her 42 years of examining human remains.

Sorg said that her first step is to catalogue the condition of each bone before she handles them, sometimes x-raying them to see if there are any foreign objects lodged in them. Then she examines their condition, and completes an inventory of what she has, and what is missing.

“Sometimes it is necessary to clean bones so you can see the surfaces better. Then you look at every single bone to rule out any sign of trauma, and to better understand what happened after death,” Sorg said.

There’s a “decreasing curve” when it comes to how much can be learned from remains that have been degraded by time and exposure. Yet, there is almost always something that can be learned, she said, citing a case where she had cremated remains that she was able to glean some information from.

Fans of crime procedural dramas might ask, “what about DNA?” Sorg responds, “We have two basic kinds of DNA.” One is nuclear DNA, found in the nucleus of nearly all cells in the human body. That’s the DNA that can be used to identify a specific individual. However, that DNA is only available when the remains are “fresh,” said Sorg, either because the person only recently died or because the remains were situated in freezing or very cold conditions.

If nuclear DNA is recovered, it can be quickly analyzed because of the many crime labs that exist to process it.

“Then we have mitochondrial DNA,” which, in terms of forensics, is the opposite of nuclear DNA. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down through mothers, so it can only shed some light on certain characteristics of the person’s mother DNA -- but it’s not the mother’s complete genome, so it can’t be used on its own to identify the mother.

Mitochondrial DNA is much more robust than nuclear, so it is much more likely to be recoverable on a given sample -- it can even be found on prehistoric remains. But it takes longer to get analyzed, because only a handful of laboratories are specialized to process it.

A worthwhile challenge

The task of recovering and identifying human remains can be difficult, but, for those whose phones ring when such a discovery is made, it’s well worth their time and talents.

“I enjoy problem solving, each case is unique,” said Sorg. “It really offers a chance to do some good, and at the same time it’s intellectually very interesting.” She declined to speak about specific cases, but said that she has recently helped to solve cold cases that had been unsolved for decades.

“I think it’s an important job to get unknown individuals identified, that’s the primary job,” Sorg said.

The months-long delay in waiting for identification can be frustrating to the public, but Fogarty said it’s better to wait for a certain answer.

“A great deal of effort is put forth to positively identify remains so we can be absolutely certain that the person that we’ve found is who we think it is,” Fogarty said. “We try not to assume anything. We try to use all of the evidence available to us,” he added.

“It’s worth it to do that, one for closure to the family and two, so that the remains of the person we’ve found are identified and we can be confident that the remains we’ve found don’t belong to someone else,” Fogarty said. “We start at ground zero and don’t assume anything. We let the evidence lead us where it leads us.”

Morse, at Fish and Game, said he and his officers consider the recovery of human cadavers to be part of their duty.

“For us, it’s kind of rewarding to bring the case to closure and finish it,” Morse said, noting that it’s often a “team effort” involving local police, state police, Fish and Game officers and forensic experts. “It’s what we do… we want to get the job done and do it right.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.