John Broderick’s older son Steven — whose real name was not used in this story at the request of his family — was a happy kid. He had neighborhood friends, loved to draw, did well in high school. “He was one of the brightest people I’d ever known,” Broderick said.

But Steven began drinking in college, and his alcohol use increased to daily while in graduate school in Boston. After he earned a master’s degree, Steven got a job quickly, but was let go after six months. He lost a second job, too, and then moved home.

A counselor told Broderick — a lawyer and trial judge for decades — his son was an alcoholic, and encouraged he and his wife, Patricia, to take the tough love route. Thinking it was best for their boy, they asked him to leave home. After three weeks, he returned with no change in his behavior, and one night in 2003, Broderick challenged his son for his drunkenness.

Steven turned on his father, beating him so harshly Broderick ended up in intensive care at Elliot Hospital in Manchester for eight days.

Steven was taken to Valley Street Jail. He was 29.

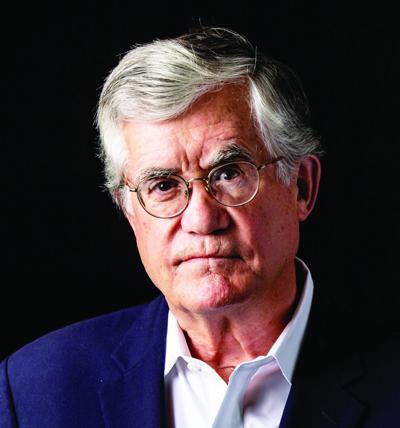

Broderick was 53, and serving as chief justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court. He knows now Steven had a significant anxiety problem, had panic attacks, and used alcohol to mask his symptoms.

“It’s hard for me to believe now that no friend or family friend or professional suggested my son could have a mental health problem. It never came up,” Broderick said. “I remember my wife and I just cried. I don’t know the technical definition for hopelessness, but I do know what hopelessness feels like. It was a horrible time.”

Struggles, despite stellar background

Over the course of his career, Broderick spent 22 years as a trial lawyer, and 15 as a judge, including six as chief justice of the state Supreme Court. Upon his retirement as a judge, he became dean and president of the University of New Hampshire Law School for five years, then worked at Dartmouth Hitchcock for five years in the mental health realm, which he continues to do. He also launched the Rudman Center for Justice, Leadership and Public Policy at UNH Law School in late 2013.

Since 2016, Broderick has been telling the story of his family’s experience with mental health trauma across New England to raise awareness about the need for a unified mental health system in this region, the state and the country.

He has spoken almost 900 times at 370 middle and high schools in New England, and at conferences in Florida, Kentucky, Pennsylvania and, most recently, Wisconsin. The presentations are under the umbrella of the REACT Awareness Campaign at Dartmouth Health, where Broderick was the senior director of external affairs, and is now a consultant.

His next local appearance is Wednesday, Oct. 22, at Lakes Region Community College, as the keynote speaker for a daylong Equipped to Care mental health symposium co-sponsored by LRCC, the Lakes Region Chamber of Commerce and the New Hampshire Teaching, Learning, and Leading Association, formerly known as New Hampshire Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

“People are starting to realize that it’s a very real everyday problem,” Broderick said. “Nowhere is that more evident than with young people.”

Symposium to raise awareness

Equipped to Care is designed for educators, business leaders, human resources professionals, community stakeholders and others on the frontlines of fostering mental wellness in schools and workplaces. It will run from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., and in addition to Broderick and nine other featured speakers, the agenda will include breakout sessions and panel discussions, exploring the connection between mental health and professional responsibility.

Other featured speakers are Mark Belanger, member of the New Hampshire Behavioral Health Workforce Center Team at Dartmouth Health; Scott Laliberte, retired school leader and author who develops programming for leaders to prioritize their personal wellness and capacity; Jeff Levin, life coach who works with teens, parents, coaches, teachers and employers; Katie Pagnotta, mental health therapist, author and consultant; Corey Gately, director of Substance Use Services for Concord Hospital; Josh Ritson, prevention coordinator at the Partnership for Public Health; Daisy Pierce, executive director of Navigating Recovery; and Eileen Glover and Celyne Godbout, peer support trainers in the Community College System of New Hampshire.

Given significant wellness concerns regarding local youth, the event is intended to provide participants with insights, resources and strategies to create a positive impact in the community.

“The goal is to try to raise awareness of some of the real challenges there are in the space of mental health, and to try to connect community leaders, members of the workforce, businesses and educators with resources,” said Steve Tucker, workforce development manager for LRCC. “John is a powerful speaker on the issue of mental health. He can show the audience the need ... and illustrate the magnitude with the goal of trying to do something about it.

“We’re excited about engaging the community on a topic that’s really important.”

To register for the symposium, visit nhtlla.org/event/2025-mental-health.

Learning in the most painful way

Broderick was not aware of what happened to Steven until he left the ICU and saw his wife for the first time in over a week. She told him about the incident with Steven, and that was the first he knew his boy was in jail. Broderick wasn’t allowed to see Steven for six months, until they found themselves in court — for sentencing.

“He gave me a hug and apologized,” Broderick said. “I said, 'If you don’t quit, your mother and I won’t quit.'”

In treatment in prison, Steven was sleeping through the night — which he hadn’t done since he was a child. He could focus, because he wasn’t panicked. He was seeing a counselor regularly and taking medication. He taught English at the prison and scored two points below genius on an IQ test there.

“When he told me that, I knew we had failed him,” Broderick said. “I should have known something about mental health.”

Steven served six years and six months of a 7.5- to 15-year sentence, and has now been sober for many years. He is married and living well.

While painful and traumatic, the event helped thousands of people who hear Broderick speak.

“People are learning from me — I hope — that it’s OK to have been doing the wrong things the wrong way. It’s OK to stop stereotyping people and understand that nobody with a mental health problem chooses it,” Broderick said. “We need to open our minds and hearts and change our attitudes and develop a mental health system in this state and country.

“We can call 911 for physical problems,” he added. “Who do you call for your mental health? How will they be serviced, and who’s going to pay for it? We’re still asking those questions in 2025.”

The message stays the same

Broderick says his message hasn’t changed over nine years, because nothing has changed in the system, and there is still stigma around mental health.

“A lot of what I’m seeing is culturally and socially driven. We are living in a world where everyone runs 20 minutes late for life, and it’s having an impact on our children,” he said. “Our focus on achievement and success and sports prowess is not healthy. Technology is crippling young people — and adults.

“Kids don’t just go out and play. What are we doing to childhood? We’ve taken imagination away.”

Commitment to community education

Tucker says the theme of community, while not part of the LRCC mission statement, is woven into the college’s philosophy. “We have a mission to be engaged and support the community. It’s absolutely an important part of what the college is about.”

He notes LRCC is intentionally working to provide educational opportunities in the human services arena, and received a state grant for peer support training along with two other community colleges.

“That’s been a successful program,” he said. “It ends in certification by the state Department of Health and Human Services. It’s a program we have run, and we are continuing to run.”

No end in sight

Broderick is 78 now, and he doesn’t see an end to his speaking engagements. “As long as the invitations keep coming, I’ll keep talking,” said Broderick, now of North Andover, Massachusetts, whose audiences range from lawyers, judges and legislators to social workers and high school students.

Strangers, friends, children — many people — talk to him continually about their mental health.

“I’m not ignorant anymore.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.