One summer morning in 1977, with my friend Scott, I set up a line of yellow poly cones on Currier Hill Road in Gilmanton, so we could slalom through them on skateboards. After five minutes, an old guy named Link Riggs came along in his pickup. Seeing the cones, Link accelerated, plowed over every one of them, then chewed us out. “What the hell are you boys doing?” he said as Scott and I stood there, silent and cowed. “This is a public road!”

I was 13 at the time, and I could spend the rest of this essay discussing the trauma I incurred from Link’s reprimand. I could, alternatively, suggest that his tirade had a corrective effect — that, from that day forward, I toed the straight and narrow and took pains to avoid doing stupid things on the roads of the Lakes Region.

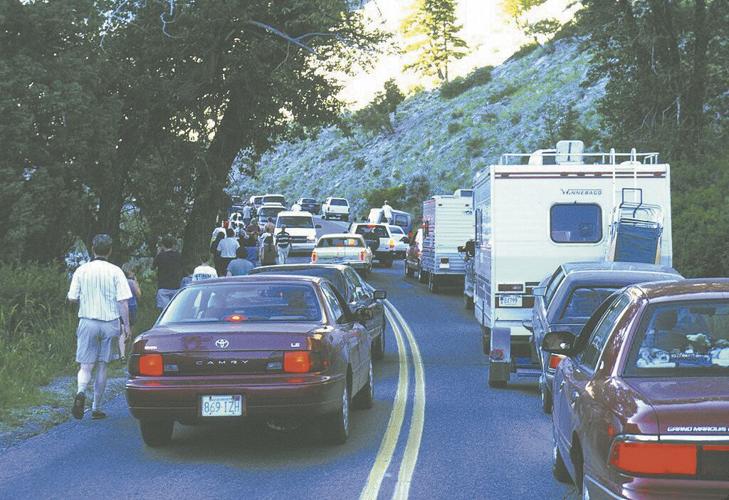

A part of me wishes that I did absorb Link’s lesson — and that I decided, early on, to stay off our local roads, at least in the summer. For between Memorial Day and Labor Day, the roads here are toxic — hot, chockablock with traffic and filled with flatlanders towing jet skis up to their cottages, everyone surly, everyone chucking half-full cans of Monster Energy drink out the window. Would I be better off if, in deference to Link’s tirade, I spent the summer months inside, hiding under my bed?

My life would be more tranquil, certainly. Perhaps I’d even have enough free time to read Marcel Proust’s seven-volume masterpiece "Remembrance of Things Past." But my problem is, I kind of love the dark high octane energy that prevails on the roads here in summertime. My ardor for it spikes when I’m out on long bicycle rides, as I was one scorching day last July. I stopped at the Beanstalk, a giant convenience store a half mile or so from the NASCAR track in Loudon, to buy an aqua Gatorade. As I sat on the curb outside the store, savoring the drink’s cool sweetness, the aroma of gasoline danced in the air. A motorcyclist pulled in, AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” blasting from the bike’s speakers, and nearby some guy with a boat trailer was doing a complicated backing-up maneuver that involved loud beeping sounds.

I should have been annoyed, but no, I felt invigorated. I felt as though I was watching summer rise to a crescendo. Maybe because I’m a writer, I reveled in thinking, “Of the 75 people stirring about this convenience store, at least one will get in a fight tonight. One will fall in love. All the stories are here.”

My taste for the roads of summer began that morning Link bawled us out. There was such brio in his indignation. His fury was bracing. It was an invitation to partake of the tussle — of the skirmish and possibility — that can live on the roads. And in all the years since, I’ve felt a sick, unmitigated hunger for that tussle, for the sort of thrill one can only get out on the roads.

When I was in high school and college, I was a distance runner. I was not a trail runner. I was a road runner, and what I loved most was running on the roads around Gilmanton at night, feeling my way along in the dark (and trying not to twist an ankle) in an age before headlamps. My taste for night running was neither logical nor sensible. Once I started a solo run of eight or 10 miles at about 9 p.m. in a thunderstorm, amid a torrential downpour. This was in the early 1980s. Punk rock was a thing, and reading Thrasher magazine, I’d learned that punks liked to stick safety pins in their ears and their cheeks. For that run, I wore a necklace wrought of interlocked safety pins — basically a lightning rod. I survived.

Scott was by now a distance runner too, and one hot summer morning I joined him and a half-dozen of his friends for a 12-mile jaunt that took us, circuitously, from Gilmanton to Laconia. Even as we shuffled out of town, warming up, testosterone was already caroming about through the pack. The pace quickened. We climbed hills and galloped down. We passed barking dogs and marshes and ponds. All the runners I was with that day were better than me, so by Belmont, I was audibly gasping. Still, I managed to spit out three words apropos of the blistering pace. “This,” I said, “is madness.”

A couple years ago, when I crossed paths with the hoary veterans of that run at a party, we kept dropping the word “madness,” our voices tinged with nostalgia and longing. For we all knew that my gasping utterance was not a complaint but an assertion of joy: We were drinking in the pleasures of the road that morning. With a vigor we can no longer muster. We are old now.

But the road is still out there, and the other evening, as I tucked into a group of cyclists pedaling the highway that climbs to Gunstock Mountain Resort, I found myself, near the top, jostling along with one other rider, the two of us giving all (and failing) to chase down a pack of skinny youngsters pedaling ahead of us.

We crested the road’s high point. Then, as we began to descend, a black pickup lingered behind us, so that I could hear the snarl of its engine. The driver followed us for maybe a mile, unable to pass on the twisting road, and I could sense in his closeness an impatience and anger. When he finally went by, he blew an angry plume of black “coal” in our faces, so for the final plunge to Route 11, I was teary-eyed and half blind.

At the bottom, stopped and catching my breath, I hated the pickup driver, for his assault on us was premeditated. A driver can’t blow coal until he first drops a few hundred bucks on modifying his diesel exhaust system. This guy had spent the money with the expectation that he would soon go looking for people to harass. And he is just one of thousands of coal rollers now lurking our nation’s roads, each one of them freighting so much menace that Link Riggs seems, in comparison, old-timey, quaint.

Our country is far more divided than it was in 1977. Hostility lurks just under the surface these days, and we all feel it out on the roads. Numerous statistics make clear that, since the pandemic, road rage has risen sharply. Tailgating and speeding are more common, and increasingly motorists are even drawing guns on one another. We’re treating ourselves with the same unthinking inhumanity we deploy when we post nasty comments on Facebook.

Resting roadside, waiting for the sting to fade from my eyes, I felt frustrated to be living in a harder world. I also felt, I have to be honest, a little bit happy. I was out on the roads. And I was, delightfully, in the thick of the tussle.

I got back on my bike and kept rolling along.

•••

Bill Donahue has written for Outside, Harper's, The Atlantic and The Washington Post Magazine. He lives in Gilmanton and is the author of "Unbound: Unforgettable True Stories From The World of Endurance Sports.” This column is adapted from his online newsletter Up The Creek.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.