LACONIA — Nearly 50 years after he went missing while serving in Korea, Laconia native and U.S. Army Pfc. George A. Curley Jr. has finally been accounted for, and he’s coming home.

The remains of Curley, who was killed at age 18 while serving in the Korean War, were identified on March 3, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Staff at the agency sent out notice in late April, after delivering a full briefing to members of Curley's family. His remains will be buried in Laconia in June.

Curley was assigned to headquarters and service company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, 2nd Infantry in December 1950, but had been reported missing somewhere in the vicinity of Sonchu, North Korea, on Nov. 30, 1950.

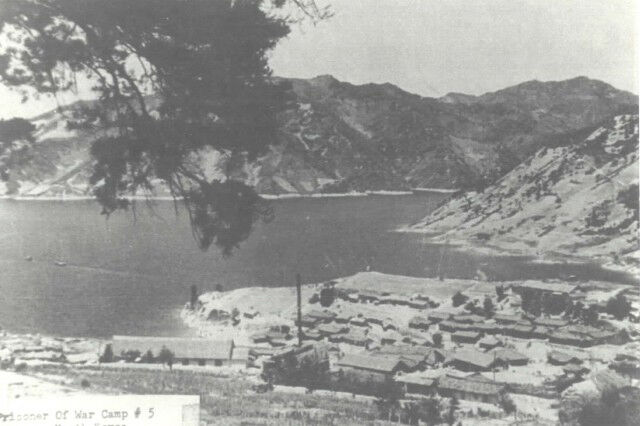

According to information obtained from prisoners of war returning home, U.S. Army officers determined he died in captivity at Camp 5 near Pyoktong, North Korea, in March 1951.

During Operation GLORY in September and October of 1954, the United Nations Command and the Chinese Communist Forces exchanged the remains of fallen service personnel. Following the processing of those remains by workers at the Central Identification Laboratory in Kokura, Japan, the lab was unable to positively associate any of the remains with Curley.

In 1956, all unidentified remains — including one designated as X-14692 — were transferred to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu, Hawaii, and interred as “unknowns”.

In July 2018, POW/MIA agency staff proposed a plan to disinter 652 Korean War "unknowns" from Honolulu and, on Nov. 18, 2019, personnel did so, including with the remains of X-14692 as part of Phase II of the Korean War Disinterment Plan. Those remains were sent back to a POW/MIA agency laboratory for further analysis.

In identifying Curley, scientists used dental and anthropological analysis and a chest radiograph. Scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA and mitochondrial genome sequence analysis.

In accordance with tradition, Curley’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with many others who are missing from the Korean War, and a rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he’s now accounted for.

Family members and loved ones should contact the Army Casualty Office at 800-892-2490 for funeral information.

Not much is known regarding Curley’s specific experience at Camp 5 near Pyoktong, but a lot of information regarding that camp is available.

According to now-declassified Central Intelligence Agency documents, Americans lived among other United Nations forces in that camp — and many others — and suffered from malnutrition and illness, and were subject to daily reeducation efforts made by North Korean and Chinese military cadres in hopes of converting some to communism.

According to an intelligence report written in February 1953, the United Nations POW camp at Pyoktong comprised 20 grass-roofed houses and 10 stone houses, and the South Korean POW camp comprised 30 grass-roofed houses, 15 stone houses and five “Korean tile-roofed” houses. Between them, there were approximately 3,000 prisoners. About 1,000 of those were American service members.

The camp was under the control of a joint Chinese Communist and North Korean army unit, which was led by a Chinese Communist officer.

United Nations prisoners, including the 1,000 Americans, were guarded by about 80 Chinese Communist soldiers, while South Korean soldiers were guarded by 70 North Korean soldiers. Guards, armed with automatic rifles, submachine guns and Japanese Imperial Army rifles patrolled the camps, which were not enclosed by barbed wire, but were overlooked by 17 guard posts spaced 50 meters apart. Those posts surrounded the camp with one exception — the northwest section, which bordered the Yalu River.

There were 30 guards on duty at all times, each one serving three, two-hour shifts each day. One officer and two enlisted soldiers patrolled the camps twice a day and once every hour at night, according to the report. In the event of trouble, three rifles were fired to summon all guards.

Until November 1951, all UN POWs received 300 grams of soy beans and 300 grams of corn each day. Starting in December 1951, POWs received 700 grams of grain, and corn was replaced with wheat flour for the UN POWs in response to issues associated with poor digestion and malnutrition. Four prisoners and two guards picked up the grain, which was issued every 10 days. Prisoners gathered firewood for cooking in the mountains once a week — the rest of the week was passed by taking indoctrination classes and performing military training drills.

Every other day, music and dance parties were held as an outlet for recreation.

By February 1953, there were no medical facilities at the camp. On average, 80 South Korean and 50 UN POWs fell ill each day, and approximately four would die. The death rate among UN prisoners was about 2% higher than that among South Korean prisoners, and the dead were buried in the nearby Pyoktong County cemetery. Typhoid, diarrhea and other diseases ran rampant through the camp.

Contact between South Korean and UN prisoners was strictly prohibited. The report notes that while relations between South Korean prisoners and guards was generally good, the UN prisoners and guards looked down upon one another.

Daily life in the camp was strictly regimented. Reveille occurred each morning at 6 a.m., roll call at 6:30 a.m., breakfast at 7 a.m., followed by indoctrination lessons between 8 a.m. and noon. Lunch was between noon and 1 p.m., more indoctrination lessons were taken between 2 and 3 p.m., recreation from 3 to 5 p.m., free time 5-6 p.m., and dinner from 6 to 7 p.m. Self-criticism from 7 to 8 p.m. was followed by free time until 10 p.m., when it was lights out for the night.

Indoctrination lessons included world and Korean political affairs and Marxism. According to reports, between 5% and 10% of South Korean prisoners converted to communism and about 2% of UN prisoners did the same. Prisoners were often required to make public speeches, declaring their support for communism, though many did so insincerely.

Since 1982, the remains of over 450 Americans killed in the Korean War have been identified and returned to their families for burial with full military honors, according to the POW/MIA Accounting Agency. That number is additional to the roughly 2,000 Americans identified in the years following the end of hostilities, when the North Korean government returned 3,000 sets of remains to U.S. custody.

There are still more than 7,500 Americans unaccounted for.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.