(Photo by Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz via Pexels)

By Stephen Beech

Wolves eat more bone to cope with climate change, reveals new research.

Fossil evidence has shown how grey wolves adapt their diets to deal with global warming.

The carnivorous predators eat harder foods - such as bones - to extract nutrition during warmer climates, according to the study.

Researchers say their findings, published in the journal Ecology Letters, have implications for wolf conservation across Europe and beyond.

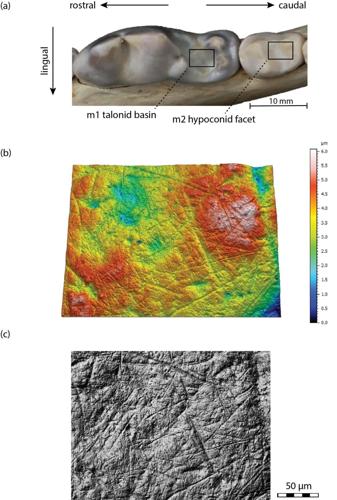

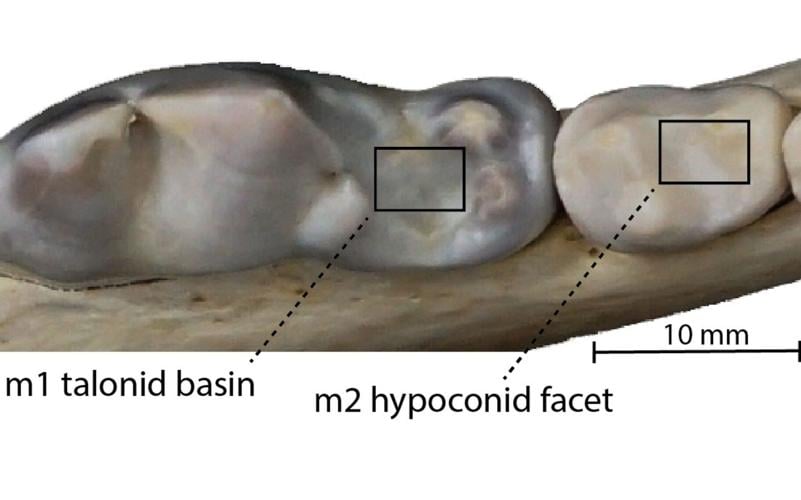

The team, led by University of Bristol scientists in collaboration with the Natural History Museum, London, compared the teeth of grey wolves from three different time periods using a method known as Dental Microwear Texture Analysis (DMTA).

They examined samples from around 200,000 years ago, a period with summers similar to today but colder winters; from around 125,000 years ago, when summers were warmer than today and winters were milder; and from modern-day wolves in Poland, where winters are becoming warmer and snow cover is declining.

Top: photograph of the area of analysis on the molar teeth; middle: topographic contour scan of the tooth surface to show microwear features from consuming hard foods (modern wolf, Poland); bottom: greyscale photo simulation of the same. (Amanda Burtt via SWNS)

Using DMTA, the researchers studied microscopic scratches and pits on wolf molars that record the animal’s diet in the final weeks or months of its life, sometimes called the ‘last supper’ effect.

Study co-author Professor Danielle Schreve, from the University of Bristol, said: “The DMTA results from fossil wolves from the two interglacial periods were very different.

“Tooth surface features indicate that the dietary behaviour of wolves from the older interglacial included the consumption of less hard food than those from the younger interglacial period.

"Wolves during these warmer temperatures appear to have been consuming carcasses more completely."

She added: “The real surprise was that modern wolves from Poland, where climate warming is also ongoing, show the same patterns as those from the younger interglacial, highlighting that they are also experiencing hitherto hidden ecological stress."

Schreve said the results showed a "clear and consistent" pattern: wolves living in warmer climates ate harder foods, including bones of carcasses, a behavior known as durophagy.

(Photo by patrice schoefolt via Pexels)

Lead author Dr. Amanda Burtt, from Bristol’s School of Geographical Sciences, said: “The findings suggest wolves were working harder to extract nutrition during warmer climate periods, scavenging more extensively or consuming parts of prey they would normally avoid."

She added: “The findings have major implications for wolf conservation across Europe and beyond.

"Grey wolves are often assumed to be resilient to climate change, but this research shows that warming temperatures should be considered a significant factor in conservation planning.”

The researchers explained that wolves thrive in cold, snowy winters.

Deep snow makes herbivore prey more vulnerable, limiting their prey’s access to food and reducing their ability to escape predators.

Wolves are also more agile on snow and ice, and colder winters are associated with heavier wolves and higher pup survival.

But warmer winters with less snow cover disrupt that balance, making hunting harder and forcing wolves to compensate through riskier or more energetically costly feeding methods.

In Poland, wolves are currently able to offset some climate-related stress by hunting deer and wild boar near farmland and by scavenging roadkill.

Top: photograph of the area of analysis on the molar teeth. (Amanda Burtt via SWNS)

Ironically, the researchers say wolves living farther from human-modified landscapes may face greater challenges in the future due to limited access to alternative food sources.

Study co-author Dr. Neil Adams, curator of fossil mammals at the Natural History Museum, said: “The fossil wolf teeth involved in this project include some that have been part of the national collection for over 175 years."

He added: “Amid the current biodiversity and climate crises, it is more important than ever that fossil specimens in museum collections are leveraged to their full potential in studies like ours focused on conservation palaeobiology.

"This emerging field seeks to apply knowledge from the fossil record to modern issues of nature conservation and restoration.”

The research team concluded that climate change should be factored into long-term strategies for conserving large carnivores.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.