![]()

Is sodium good or bad for you?

Hypertension has been an established heart disease risk factor for decades. When blood flows at normal pressure, your vessels stay strong and flexible. Cranked up too high for a long period of time, this pressure can damage your vessel walls, making them stiff and narrow — ultimately increasing your risk for a cardiovascular event like a heart attack or stroke.

Where does sodium come in? You likely learned in high school chemistry that this mineral, a component of salt, retains water. In your blood vessels, more volume means more pressure.

The U.S. government’s sodium intake recommendation of 2.3 grams per day leans heavily on this chemistry lesson, all in the name of heart health.

But this blanket recommendation is largely based on observational data — rather than controlled clinical studies — reporting higher sodium intakes are linked to higher blood pressure in certain populations.

The problem: Sodium also happens to be a critical component of heart health and overall well-being. Your body — and that includes your cardiovascular system — literally couldn’t function without it.

So it’s not surprising that other studies paint a different picture about this key electrolyte, linking higher salt intakes to less hypertension and a lower risk of death from stroke or heart attack.

Given the lack of large clinical trials forging a stronger link between sodium and heart disease risk, a 2020 study goes as far as questioning blanket sodium intake recommendations, instead focusing on reducing processed foods that happen to be high in sodium. Of course, it’s always a good idea to check in with a trusted healthcare provider to understand and minimize your personal cardiovascular disease risk.

Sodium certainly isn’t a panacea — and more isn’t always better for every individual. But the latest nutritional science we’ll explore in this piece suggests that the USDA’s two gram recommendation is lower than what may be optimal, or even healthy for some.

Read on for a deep dive from LMNT about sodium’s critical function in the body, and how you can leverage this electrolyte for your well-being.

What Sodium Does

Let’s get something straight: Sodium is not an optional mineral. Even low-salt advocates aren’t calling for zero sodium.

Every time the brain sends a signal through the nervous system, it does so using an action potential, or an electrical pulse. This pulse is made possible by sodium-potassium pumps that move sodium and potassium ions in and out of nerve cells to create the electrical charge needed for the signal.

The main functions of sodium in your body include:

- Conducting nerve impulses in your brain and nervous system.

- Regulating fluid balance outside your cells (i.e., helping your blood flow).

- Maintaining healthy blood pressure.

- Helping transport nutrients through your gut.

At the bare minimum, everyone needs around 500 milligrams (mg) of sodium daily to squeak by (though the bare minimum says nothing about optimal intakes).

If you don’t have the sodium you need to function — say your diet is very low in salt — your body actually goes into sodium-sparing mode. This is when certain hormones — such as aldosterone — kick up and you pee out less sodium.

High-salt diets have the opposite effect, causing you to excrete more sodium, but this story will get into that in a bit.

The History of Low-Sodium Recommendations

You might be wondering: If sodium is so important, what’s with the blanket recommendations against it?

It started with Lewis Dahl, a research scientist who published a number of papers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Back then, he discovered that rats with certain genes — now called “Dahl rats” — would develop high blood pressure at high salt intakes. Dahl fed the rats the human equivalent of 560 grams of salt per day. That’s like ingesting a pound of salt in a 24-hour period. Not surprising, right? Chemistry 101.

Dahl also found a link between sodium and hypertension in human populations. The data was observational, however — and Dahl was puzzled over the fact that many individuals on high-salt diets did not have high blood pressure.

Dahl’s findings were used, in part, to justify 1980 U.S. Dietary Guidelines that admonished the public to “avoid too much sodium.” These guidelines, however, didn’t say how much salt one should avoid.

This has changed. Today, the USDA recommends capping sodium at 2.3 grams per day to reduce the risk of hypertension and heart disease.

The American Heart Association (AHA) is even more bearish on salt, advising you to stay under 1.5 grams per day. For reference, the average American consumes about 3.4 grams of sodium per day — but it’s important to remember the average American also consumes a Standard America Diet (SAD) that’s heavy in processed, refined foods, which are often high in sodium.

Sodium and Blood Pressure

A number of studies (mostly observational, though some clinical) point to salt’s role in increasing blood pressure.

Physiologically, this isn’t surprising: If you’re injected with loads of sodium, it will transiently increase your blood volume, and therefore your blood pressure.

But what about normal variations in dietary sodium intake? How does that affect blood pressure over time?

The data, to say the least, aren’t consistent.

Take the Intersalt Study, published in 1988, which looked at sodium and blood pressure in over 10,000 people across 52 regions of the world.

In the vast majority of populations, researchers observed no link between sodium intake and high blood pressure. But some outlier populations stood out.

For instance, the Yanomami (native to Brazil) ate very little sodium and had — much to the glee of anti-salt folks — very low blood pressure.

To them, this correlation was data to vindicate low-salt diets. But the Yanomami aren’t exactly ideal models for the low-salt campaign.

In fact, this population dies relatively young and appears to suffer from growth issues.

This isn’t to say inadequate sodium is the cause of their health woes, but it’s not exactly protecting them from the outcomes that matter most.

Since the Intersalt Study, evidence for sodium causing high blood pressure continues to underwhelm.

In 2017, researchers analyzed 2,632 people with normal blood pressure consuming either low (under 2.5 grams) or high (over 2.5 grams) sodium intakes. Guess what? The high sodium group had lower blood pressure than the salt restrictors. This simply couldn’t happen if more sodium always meant higher blood pressure.

Further, there may be some confounding factors affecting the conversation about salt and cardiovascular risk. As mentioned, the SAD is ridden with processed foods that are also notoriously high in sodium.

Plus, people eating more sodium also tend to consume more sugary soft drinks.

Metabolic syndrome, which stems from insulin resistance — you guessed it, often as a result of sugary, processed foods — is another well-known risk factor for heart disease.

On the flipside, when people eat more whole foods, they naturally eat less sodium. They also tend to be people who exercise more — a lower-risk group when it comes to heart disease.

So could it be that salt is unfairly taking the heat, when metabolic syndrome is a far more pressing problem?

The Potassium Connection

A subset of the population is genetically prone to hypertension at high salt intakes. These people are referred to as “sodium hyper responders,” and their data is intermingled with everyone else’s — likely driving many positive correlations between sodium intake and blood pressure.

Should salt-sensitive people avoid salt, then? Not necessarily. They may actually do better to increase potassium — another crucial electrolyte abundant in fruits and vegetables.

When salt-sensitive people eat enough potassium (3.5-5 grams per day is a good evidence-based target), it often neutralizes the effect of sodium on blood pressure. This effect also occurs, to a lesser extent, in the rest of the population.

Inadequate potassium could explain some data linking high-sodium diets to hypertension.

High-sodium diets tend to be full of refined foods, which are notoriously devoid of potassium. Food quality matters tremendously, and it should be a far bigger part of the heart health conversation than it is.

So, Does Low Sodium Actually Help Your Heart?

The case for sodium restriction lowering blood pressure is tenuous at best. But even if you buy that argument for a moment, what about the outcomes that really matter? Do low-sodium diets actually prevent heart attacks, strokes, and cardiac death?

One of the best answers to this question was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

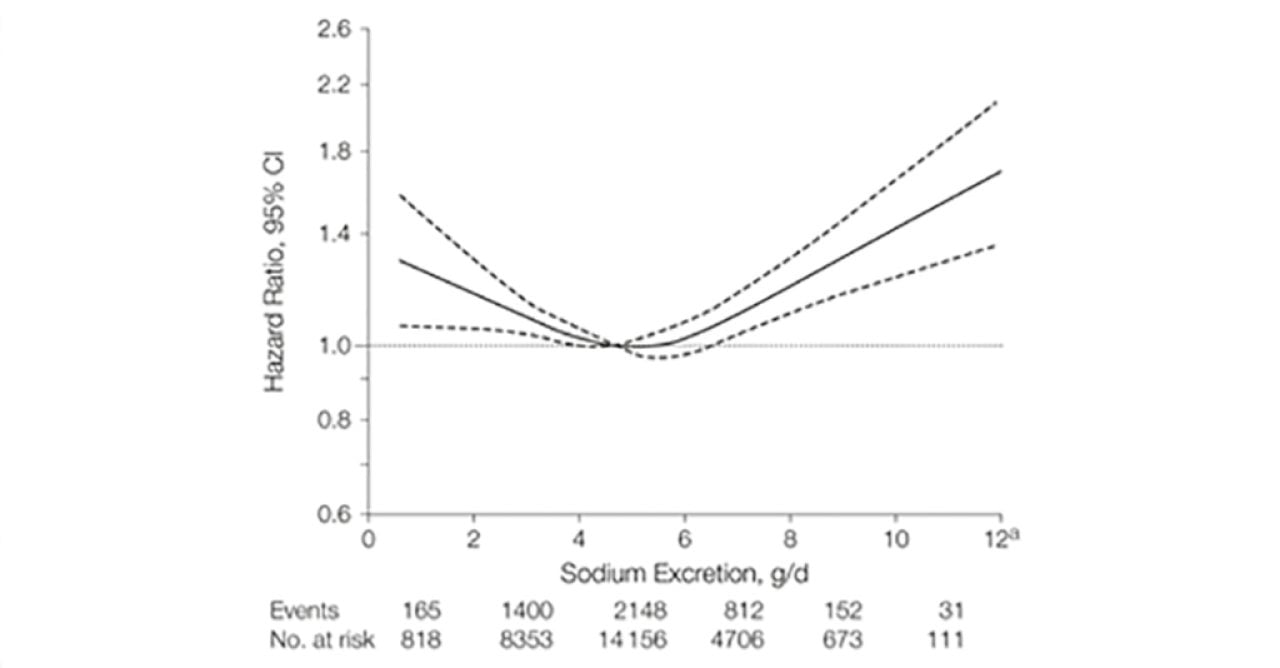

Researchers followed 4,729 heart disease patients over several years, routinely measuring sodium excretion as a proxy for sodium intake.

When the study wrapped, 2,057 of the patients had died from stroke, heart attack, and other cardiac-related deaths. Researchers then plotted the risk of death data against the sodium intake data:

As you can see, the lowest risk of death (bottom of the U) aligns with about 4-6 grams of sodium excretion per day. Travel left from this spot to lower sodium excretion and the death risk shoots up.

Note, however, that sodium intake and excretion are different, and we aren’t able to pinpoint the sodium intake of the study participants. So this study’s findings should be taken with a grain of, well, salt.

This study sits within a broader discourse about how sodium intake is best measured. The Kawasaki equation is commonly used in large studies because it’s far easier than tracking exactly how much salt people eat and how much they lose. But it’s not perfect — it doesn’t capture the full picture, especially when it comes to how the body might be holding onto or losing sodium in ways that don’t show up in urine samples. Very few studies look at both intake and excretion together, largely because they’re expensive and complex to run. So while this method is widely accepted and the findings are helpful, they should still be interpreted with some caution.

More recently in 2018, researchers reviewed a number of clinical trials on low-sodium diets for treating heart failure. They found no solid evidence to support low-sodium diets.

At least according to this data, low-sodium diets don’t directly improve heart health in this population — and that’s why one-size-fits-all recommendations are likely not useful.

Surprising Symptoms of Sodium Deficiency

Headaches, brain fog, fatigue, and irritability can be commonly caused by an electrolyte imbalance and sodium deficiency.

When you restrict salt, your kidneys go into sodium-sparing mode. In other words, you pee out less sodium.

Think of it like wartime rations. When sodium is scarce, you save some for later. Your body is smart like that — hard-wired to survive scarcity of all types, be it food or sodium.

Preserving sodium, however, comes with consequences. Namely, a flood of hormones, including the following.

- Renin: Helps regulate blood pressure by triggering a chain reaction that narrows blood vessels and signals the body to retain sodium and water (effectively increasing blood pressure).

- Aldosterone: Also helps control blood pressure by signaling the kidneys to retain sodium and water while excreting potassium.

- Norepinephrine: Plays a role in the stress response and increases levels of renin — which, as explained, can boost blood pressure.

But the biggest danger of low-sodium diets? They increase the risk of hyponatremia (low blood serum sodium) and the muscle cramps, fatigue, seizures, confusion, and brain damage that often come along with it.

By itself, a low-sodium diet probably won’t cause hyponatremia. The main causes are:

- Heart failure

- Kidney disease

- Liver disease

- Cancer

- Diuretic usage

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Overhydration with plain water (water dilutes cells, in turn diluting sodium)

But getting enough sodium gives you a baseline of protection, especially against the exercise-associated form of hyponatremia.

A few populations in particular must work extra hard to get enough sodium and avoid this condition, including:

- Athletes, especially endurance and high-volume trainers, who lose lots of sodium through sweat. The Journal of Sports Science estimates that athletes have daily sodium losses of 3.5-7 grams. Note: this is in addition to their baseline sodium need.

- People who work outside in hot, sweaty conditions, such as construction workers or landscapers — especially those hydrating with plain water.

- Low-carb or keto dieters, who excrete extra sodium thanks to low insulin levels.

- Those who practice fasting, who lose lots of sodium due to the natriuresis of fasting.

To determine if you might need more sodium, think through your daily routines and how you feel.

If you fall into any of the above categories and your performance is lagging, you’re having a tough time sleeping, or you feel dizzy when you stand up, supplementing sodium with an electrolyte powder, or smart dietary sources like olives or pickles may be a good idea.

So, what’s the right amount of sodium for you?

The government says to stay under 2.3 grams.

The average American eats about 3.4 grams.

And the sweet spot for outcomes may be closer to 4-6 grams of sodium excretion per day.

No guideline applies to everyone: Blanket recommendations aren't helpful. But when you look at the data on sodium, it suggests that many people could do well with salt, not less.

Always consult your doctor if you have serious medical conditions prior to starting any supplementation.

Explore more with science-backed guides on how to stay hydrated and electrolyte-rich foods.

Key Takeaways

- Sodium is an essential mineral that supports numerous critical bodily processes, including cardiovascular function.

- Too much sodium can certainly increase blood pressure, and blood pressure is a known risk factor for heart disease. But new research suggests sodium is unfairly blamed as the main driver of heart disease.

- Blanket recommendations promoting low sodium intake aren’t helpful for everyone in reducing heart disease risk — nor will they support low blood pressure across the board.

- When salt-sensitive people eat enough potassium, it has often been shown to neutralize the effect of sodium on blood pressure.

- Some people lose more sodium than others — especially athletes, outdoor workers, low-carb dieters, and those who fast. If you’re in one of these groups and feel sluggish, dizzy, or can’t sleep well, you might need more salt.

- At the bare minimum, everyone needs around 500 milligrams (mg) of sodium daily. But many metabolically healthy folks may benefit from closer to 4-6 grams (g) — or 4,000-6,000 mg — of sodium excretion every day to replenish what’s lost due to age, climate, activity level, and more.

- Understanding how sodium works in the body, where the USDA recommendations came from, the latest nutritional science, and your own unique sodium need is the best way to ensure you get the right amount of this key electrolyte.

This story was produced by LMNT and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.