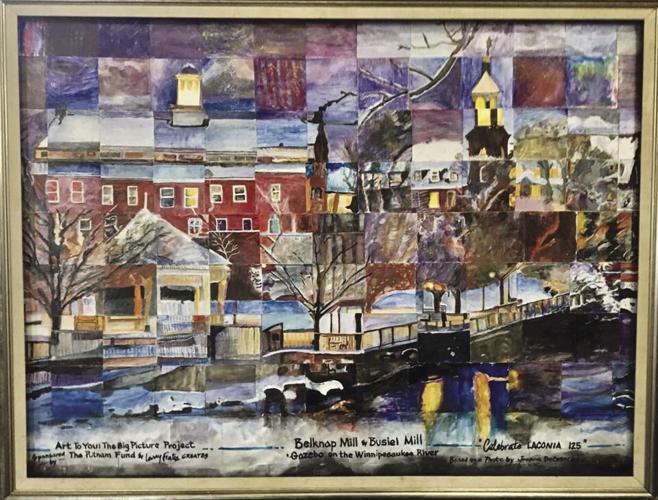

LACONIA — The Belknap Mill turns 200 this year.

As the oldest unaltered brick textile mill in the United States and the official meetinghouse of New Hampshire, its age alone is something to celebrate. But beyond what a blurb might include about its landmark status, the building is a living metaphor for the story of Laconia, for how mills — like mill cities — must learn to reinvent themselves from within in the face of obsolescence.

The history of the Belknap Mill can be understood in two distinct eras, before and after its closure in 1969. At that time, it joined much of the rest of downtown on the chopping block for demolition — the grittier parts of its not-so-distant industrial past are some many city residents were keen to move on from, and the rush toward renewal was sweeping. The eventually successful grassroots push to save the mill from the wrecking ball became a re-founding impulse that continues to define its identity. In its more recent era, the mill magnetically drew the talents and passion of community members — including at least half a dozen mayors — who worked to preserve it as a historical and cultural jewel in the crown of downtown.

This history, said a dozen current and former board members and volunteers interviewed for this article, bears the fingerprints not only of the people who were employed by the mill in its past, but also those who have worked to forge its future.

The beating heart of a mill city

For more than 100 years, Laconia was a city built, powered and shaped by its five hosiery mills, local historian Warren Huse said. “This is the only remnant left.”

The Belknap Mill, built in 1823 and functional by 1828, began as a weaving mill and in 1861 converted to knitting. As the industrial revolution spawned manufacturing centers across New England, the geography in the area that became Laconia — it incorporated as its own town in 1855 — nurtured a web of hydro-powered mills, including those that made machines, needles, machine parts and shipping boxes for the knitting industry. The hydropower produced at the mills also, later, powered the city.

Operators working at the Belknap Mill were largely women and children, initially from farming families and then increasingly from migrants from French-speaking Canada who moved to New England because of its employment opportunities. Work in a New England textile mill was taxing and dangerous, but it also provided economic opportunity and mobility.

‘Urban removal’

By the time the mill closed in 1969, an Urban Renewal program, set in motion in the early '60s, had begun fundamentally changing the architecture, and by extension the character, of downtown.

“An unsentimental review of what Laconia's downtown actually looked like in the late 1960s discloses an overpowering number of appalling, decomposing, unsafe buildings,” reads a foreward to Ester Peters’ history of the mill. Urban Renewal efforts were built on a prevailing philosophy “that ‘old’ was bad, should be torn down and removed to make way for ‘new,’ which was modern and good, and functional.”

Remembrances of the period have soured on that attitude, even if they acknowledge the necessity of some of the modernizations. In what seemed to be a slip of the tongue, one person interviewed for this article referred to the period as “urban removal.”

This push for a fresh start was combined with conflicted feelings about the history embodied by the mill. For many whose family members had worked in the mills, that history was fresh — and complicated.

“The Save the Mills Society started out with a significant lack of community support,” recalled Rod Dyer, mayor of Laconia in the late '60s and early '70s, during the execution of urban renewal but not the planning of it. “There was some sentiment, particularly in folks that had a French-Canadian heritage, that this was a symbol of the deprivation of opportunities that the original French Canadian settlers had when they came to Laconia.

“I felt it stood for the opportunity of impoverished people to come to this country and find meaningful work,” Dyer said. He joined forces with the Save the Mills Society, led by Peter Karagianis Sr., to shield the Belknap and Busiel ills.

The push to save the mill, Karagianis’ son recounted, was born from his father’s vision to convert the mill into a center of civic life downtown, a vision in which he invested his livelihood.

“People forget that it so easily could have gone the other way,” said Jennifer Anderson, who co-chairs the Belknap Mill’s current board of directors, alongside Peter Karagianis Jr. “People assume that what others are doing is the best thing that should be done, and don't ask any questions. And next thing you know, something's gone.”

The Save the Mills Society prevailed in a dramatic, years-long struggle, facing down both the wrecking ball and a swell of public opinion behind it: the mill was placed on the National Register of Historic places and designated the state’s official meetinghouse. Through a grassroots campaign for public support and fundraising, Karagianis Jr. said, it received badly needed renovations.

Over the decades that followed, the mill built up programs to support its mission to “expand the cultural identity of the Lakes Region” by being a center for the arts, history and education. Those programs included hosting exhibits of the visual arts, series of performing arts, showcases of art from the region’s students and workshops. Its powerhouse was converted into a small museum, open to public tours and host to students in the region’s fourth grade classes. Many a political hopeful made appearances at the mill, and a tradition sprouted of inaugurating new mayors within its walls. It became a popular space for local board meetings, parties and weddings.

By the '90s, Karagianis Jr. said, “some of those naysayers, the people that just wanted it gone, often came to my father and said, ‘Pete, you did a good job. It’s something we can be proud of.’”

Balancing community vision, financial obstacles

While the image of the mill had been transformed, the physical space remained subject to the realities of old buildings, realities that posed a real threat to a nonprofit without major and constant sources of cash flow.

By the 2010s, both the need for repairs and the financial straits of the mill had become dire.

“They couldn't make payroll, basically. The roof was caving in, and there was absolutely no money to be found. And they didn't know what to do,” Anderson said.

Talk of trying to sell the mill to the city, already committed to the rehabilitation of the nearby Colonial Theatre, prompted outcry. New faces joining the board, including Anderson and Karagianis Jr., launched a capital campaign spearheaded by Karen Prior.

That campaign drew massive community support, funding a new roof, bell tower, replacement of a heating system that had unexpectedly failed, renovation of the third-floor event space and an outdoor patio dedicated to Dyer and his wife Gail earlier this year.

Looking forward, board members want to see the mill do more to realize its potential as a museum, as an arts center and as an educational offering. But doing any of those things, they emphasize, requires a firmer financial foundation than the mill has been able to achieve in the past.

When it comes to volunteers and funding, remarked longtime artist-in-residence at the mill Larry Frates, “the pool has become a puddle, and everybody is trying to get water.”

Cheryl Avery became executive director at the mill in 2022. Cresting the hill of a major capital campaign and growing out of the standstill of the pandemic, she said, it became clear the mill had to become financially stable as an organization in order to pursue the artistic, historical and educational potential it holds.

“We have to be financially viable, in a strong position. So, you know, when a rainy day comes in the future, we're able to handle it and not get flat and start neglecting the building,” Karagianis Jr. said. “Ultimately, we want to build an endowment.”

Several of the board members interviewed for this story described aspirations to renovate the building’s first floor, to expand its relationship with schools by teaching older students about the area’s manufacturing base and to regrow its artistic programming for adults and children alike. At the same time, revenue from its handful of commercial tenantsand from the weddings and events hosted at the mill are imperative to its financial security. The two efforts have to weave together without overcoming the other, Avery said.

“What I don't want to have happen is have this be an event venue that happens to have a museum attached to it,” Avery said. “I want us to be the museum and the art center that has event space.” It’s a balance that will take time to achieve.

Celebrating two centuries

Current board members describe themselves as inheritors of a collective purpose and historical appreciation first realized when the mill was saved in the '70s.

“That's pretty remarkable that someone had that sense of history,” said Mayor Andrew Hosmer, who also sits on the mill’s board. “And I think all of us here who are involved in the mill appreciate the fact that we're stewards of something that's special.”

Recognizing the anniversary, Avery emphasized, is as much about honoring the stewardship of the building as it is the history, about “recognizing the kind of care that had to be taken in this building for it to still be here.”

The mill still stands, interviewees emphasized, because of those who stepped forward to defend it in its most precarious moments.

The success of those defenders, the lessons of the mill's history, Hosmer said demonstrates Laconia’s inherent ability to believe in itself.

Like the mill, “Laconia for far too long was defined by our challenges,” Hosmer said.

"When we think about the opportunities around this place, and the history of this place," he continued, "We define ourselves by [our] possibilities, not our challenges.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.