(Photo by Brent Keane via Pexels)

By Stephen Beech

Volcanic eruptions set off a chain of events that brought the Black Death to Europe, according to new research.

Clues contained in tree rings have identified 14th Century volcanic activity as the "first domino to fall" in a sequence that led to the devastating spread of bubonic plague.

Researchers used climate data and documentary evidence to paint the most complete picture to date of the "perfect storm" that led to the deaths of tens of millions of people, as well as massive economic, political and cultural changes.

Their evidence suggests that a volcanic eruption – or cluster of eruptions – around 1345 caused annual temperatures to drop for consecutive years due to the haze from volcanic ash and gases.

That in turn caused crops to fail across the Mediterranean region.

To avoid riots or starvation, the research team say Italian city states used their connections to trade with grain producers around the Black Sea.

The climate-driven change in long-distance trade routes helped avoid famine, but as well as vital food supplies, the ships carried the deadly bacterium that ultimately caused the Black Death.

Photograph of the fresco Trionfo della Morte, taken at its original location in the Camposanto Monumentale in Pisa. The fresco, known as the Triumph of DeathÂand attributed to the painter Buonamico Buffalmacco, is not precisely dated; scholarly estimates range from 1335 to 1350. While it does not depict the Black Death explicitly, the selected detail shows victims of an epidemic from diverse social backgrounds, their souls carried off by demons. (Martin Bauch via SWNS)

The study, by researchers at Cambridge University and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Germany, is the first time that it has been possible to obtain high-quality natural and historical data to draw a direct line between climate, agriculture, trade and the origins of the plague.

Between 1347 and 1353, the Black Plague killed millions of people across Europe with the mortality rate close to 60% in some areas.

While it is accepted that the disease was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which originated from wild rodents in central Asia and reached Europe via the Black Sea region, it’s still unclear why the plague broke out when it did and how it spread so quickly.

Cambridge geography Professor Ulf Büntgen said: “This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time.

"What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they?

"Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history? It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no one can answer alone.”

Prof Büntgen, whose research group uses information stored in tree rings to reconstruct past climate variability, worked with Dr. Martin Bauch, a historian of medieval climate and epidemiology at GWZO, on the study published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

(Photo by Jeffry Surianto via Pexels)

Dr. Bauch said: “We looked into the period before the Black Death with regard to food security systems and recurring famines, which was important to put the situation after 1345 in context.

“We wanted to look at the climate, environmental and economic factors together, so we could more fully understand what triggered the onset of the second plague pandemic in Europe.”

The researchers combined climate data and written documentary evidence with conceptual reinterpretations of the connections between humans and climate to show that a volcanic eruption – or series of eruptions – around 1345 was likely the first step in a sequence that led to the Black Death.

The researchers were able to approximate this eruption through information contained in tree rings from the Spanish Pyrenees.

Consecutive "Blue Rings" pointed to unusually cold and wet summers in 1345, 1346 and 1347 across much of southern Europe.

While a single cold year is not uncommon, the researchers said consecutive cold summers are highly unusual.

Documentary evidence from the same period noted unusual cloudiness and dark lunar eclipses, also suggesting volcanic activity.

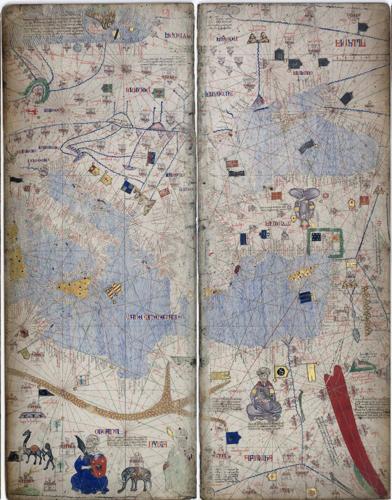

Atlas from the 14th century, attributed to Abraham Cresques. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France via SWNS)

The volcanically forced climatic downturn led to poor harvests, crop failure and famine.

But the Italian maritime republics of Venice, Genoa and Pisa were able to import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde around the Sea of Azov in 1347.

Dr. Bauch said: “For more than a century, these powerful Italian city states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation.

“But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe.”

Previous research has suggested that ships carrying the grain probably also carried fleas infected with Yersinia pestis.

Ancient DNA has suggested that there may have been a natural reservoir of the deadly bacterium in wild gerbils somewhere in central Asia.

Once the plague-infected fleas arrived in Mediterranean ports on grain ships, the researchers say they became a "vector" for disease transmission, enabling the bacterium to jump from mammalian hosts to humans.

Büntgen said: “In so many European towns and cities you can find some evidence of the Black Death, almost 800 years later.

(Photo by Archie Binamira via Pexels)

“Here in Cambridge for instance, Corpus Christi College was founded by townspeople after the plague devastated the local community.

"There are similar examples across much of the continent.”

Dr. Buach said: “We could also demonstrate that many Italian cities, even large ones like Milan and Rome, were most probably not affected by the Black Death, apparently because they did not need to import grain after 1345.

“The climate-famine-grain connection has potential for explaining other plague waves.”

The researchers say the "perfect storm" of climate, agricultural, societal and economic factors after 1345 that led to the Black Death can also be considered an early example of the consequences of globalisation.

Büntgen said: “Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalised world.

“This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with COVID-19.”

The researchers say modern risk assessments should incorporate knowledge from historical examples of the interactions between climate, disease and society.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.