(Photo by ArtHouse Studio via Pexels)

By Stephen Beech

A woman's natural scent at different times of the month alters men's behaviour around them, suggests new research.

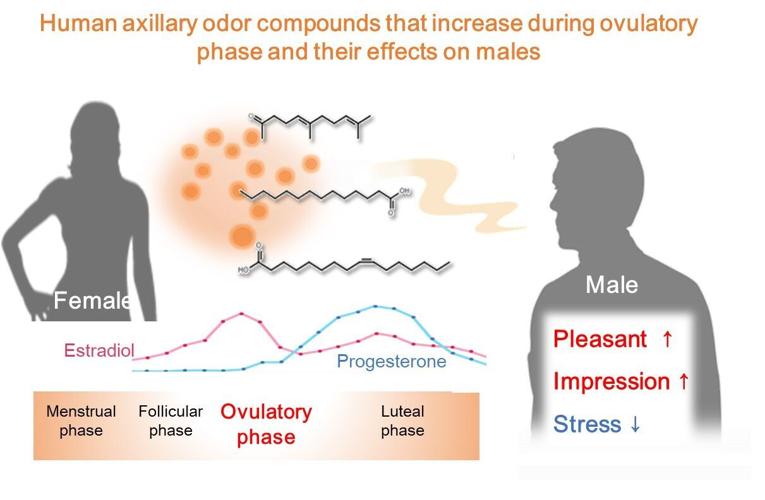

Changes in female body odor during ovulation trigger "measurable reactions" in the opposite sex, say Japanese scientists.

Researchers at the University of Tokyo explored how a woman's body scent can influence the behavior of men.

They found certain scent compounds in female body odor increased during ovulation and can subtly influence how men feel.

When those scents were added to armpit odor samples, men rated them as more pleasant and faces associated with the samples as more attractive.

The scents also seemed to reduce stress, according to the findings of the study published in the journal iScience.

The researchers say that it is not evidence of pheromones in humans, but that smell might "subtly" shape how we people interact.

(University of Tokyo via SWNS)

Pheromones - behavior-altering compounds shared between organisms - have not been demonstrably proven to exist in humans.

But the findings of the new study by the Department of Applied Biological Chemistry and the International Research Center for Neurointelligence (WPI-IRCN) at the University of Tokyo does show something is happening similar to the idea of pheromones.

Study leader Professor Kazushige Touhara said: “We identified three body odor components that increased during women’s ovulatory periods.

"When men sniffed a mix of those compounds and a model armpit odor, they reported those samples as less unpleasant, and accompanying images of women as more attractive and more feminine.

“Furthermore, those compounds were found to relax the male subjects, compared to a control, and even suppressed the increase in the amount of amylase - a stress biomarker - in their saliva.

"These results suggest that body odor may in some way contribute to communication between men and women.”

(Photo by Mental Health America (MHA) via Pexels)

Previous studies had shown that female body odor changes throughout the menstrual cycle, and that the changes in the ovulatory phase can be perceived by men and are reported as being pleasant.

But the specific nature of those odors had previously been unidentified.

Touhara and his team used a technique for chemical analysis called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and identified volatile compounds that fluctuate across menstrual cycle phases.

Study first author Nozomi Ohgi, a graduate student in Touhara’s lab, said: “The most difficult part of the study was to determine the axillary, or armpit, odor profile within a woman's menstrual cycle.

"Of particular difficulty was scheduling more than 20 women to ensure that axillary odors were collected at key times during their menstrual cycles.

“We also needed to interview each participant frequently regarding body temperature and other indicators of the menstrual cycle in order to understand and track their status.

"This required a great deal of time, effort and careful attention.

Olga Solodilova

"It took more than one month per participant to complete the collection within the menstrual cycle, so very time-consuming.”

Another challenge the researchers faced was to ensure the tests were done “blind” - meaning the participants did not receive any hints about what they were smelling or why, with some participants being given nothing at all as a measure of control.

Psychological factors and expectations can be reduced or eliminated that way, according to the researchers.

Touhara said: “We cannot conclusively say at this time that the compounds we found, which increase during the ovulation period, are human pheromones.

"The classical definition of pheromones is species-specific chemical substances that induce certain behavioral or physiological responses.

“But from this study, we can’t conclude whether the axillary odors are species-specific."

He added: "We were primarily focused on their behavioral or physiological impacts, in this case, the reduction of stress and change in impression when seeing faces.

"So, at this moment, we can say they may be pheromone-like compounds.”

The Japanese team plans to explore further the research, including broadening the kinds of people involved to eliminate the chance of a specific genetic trait influencing results, and looking at how ovulatory compounds might affect active areas in the brain related to emotion and perception.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.